Superhumans with ‘Yeti blood’: These people are able to withstand extreme conditions, and science might finally know how

As he climbed Mount Everest’s Lhotse ice wall, Sameer Nicholas Patham struggled to breathe despite his supplementary oxygen. Here, where temperatures drop to -30° Celsius and the ambient oxygen is 70% lower than we breathe at sea level, every step was torture.

But his Sherpa friends calmly and easily climbed past, carrying an average weight of 16kg. “They are superhumans,” recalls Sameer, who experienced firsthand what he describes as the incredible feats of the Sherpas, a Tibetan ethnic group globally known for their natural mountaineering skills.

Yet if the same Sherpas were to visit Varanasi and fall sick, the hospital’s doctors would find that they had high blood pressure and low hemoglobin compared to average plains dwellers. Often such Sherpas were prescribed unnecessary medication. And though Chinese and American scientists had isolated the gene that allowed high-altitude adaptation, a biochemical analysis was always lacking – until a recent deep study by a team of Indian scientists investigated how Himalayans have survived in their challenging habitat for centuries.

The Himalayans

The Sherpa people are world-famous for high-altitude living and mountaineering. According to the 2011 census, there were some 16,012 Sherpas in India. Though there are other high-altitude Himalayan ethnic groups, the Sherpas dominate the portering profession to the extent that porters are commonly called “Sherpas” by outsiders.

Other high-altitude ethnic groups include the Tibetans, inhabiting the Tibet Autonomous Region, Gansu, Qinghai, Sichuan and Yunnan in China; they are also found in India, Bhutan and Nepal. There are 182,685 Tibetans in India, scattered in Bengal, Himachal Pradesh, Arunachal Pradesh, Ladakh, Karnataka and Uttarakhand. Then there are the Lepchas, an aboriginal tribe of Darjeeling and Sikkim, in the Himalayas, calling themselves “Rong Migyit” (Lepcha people). They number 47,331. Additionally, the Bhutia tribe is scattered around the Himalayan region and number 229,954.

These peoples, with their robust physical appearance and rugged lives, have taught the world a thing or two about extreme survival in a hostile climate with low oxygen levels and harsh terrain. Despite this demanding climate, however, there is evidence of early human settlement in the Himalayas.

“While settled there for long periods, people in this region acquired extraordinary ways to fight the extreme climatic conditions in the form of mutations in their genome. Thus, there exist positive selections of several genes which ultimately are the drivers of adaptation in a harsh environment,” says Gyaneshwar Chaubey, known for his work in biological anthropology, medical genetics and forensics.

From Banaras Hindu University’s (BHU) zoology department, Professor Chaubey was part of a team from the University of Calcutta and BHU that analyzed the anthropometric and biochemical parameters of 178 individuals from ethnic tribes living at an altitudinal range of between 1,467 meters and 2,258 meters above sea level.

They found that populations at high altitudes have significantly lower hemoglobin and higher blood pressure in order to cope with the extreme climate. Comparatively low hemoglobin facilitates efficient blood circulation in populations at high altitudes, Chaubey says, enabling them to utilize less oxygen more efficiently. “At high altitudes, the low atmospheric pressure forces the heart to pump harder to effectively circulate the oxygen,” he explains.

Hemoglobin carries oxygen from the lungs to the rest of the body. At high altitudes, with high blood pressure, low hemoglobin balances the concentration of oxygen at any given moment and at any given point.

For average people, they may cause hypoxia. For Sherpa and Tibetans, however, their high blood pressure and low hemoglobin overcomes the problem. “The genetic mutation keeps their low hemoglobin [level], which acts as a natural blood thinner, and high pressure makes sure that it reaches each and every cell effectively,” Chaubey adds.

Contrast this with more than 300 climbers who have, since 1953, died on their way to Mount Everest, a third of whom succumbed to a lack of oxygen.

The study, published recently in the American Journal of Human Biology, covered Sherpas, Lepchas, Gorkhas, Tibetans and the Bhutia tribes, all of whom have made the Himalayas their home since time immemorial. The data was statistically analyzed using variance and multiple linear regression methods.

“The adaptation due to their genomic mutations has enabled them to utilize the prevailing less atmospheric oxygen levels and cold climate. However, how these genes modulate, the phenotype still needs to be discovered,” says Chaubey, emphasizing to RT the need to expand the genetic research initiated by the Chinese and the Americans.

The Yeti connection

More surprisingly, he says, the most predominant gene of this high-altitude adaptation family (EPAS1) was the result of an introgression from archaic humans, known as Denisovians, to modern humans. “Many scientists think that these Denisovians are the mysterious Yeti who exist mainly in folklore and stories,” says Chaubey.

The Denisovians were an archaic human group from 370,000 years ago, and are called such because of fossils found in the Denisova Cave in Siberia’s Altai mountains. They lived during the Pleistocene Epoch, moving throughout Eurasia, South Asia and Melanesia before disappearing 30,000 years ago.

The EPAS1 gene passed from the Denisovian genome to modern humans adapted to low oxygen, allowing modern Tibetans and the Sherpas to live at high altitudes more comfortably than others, Chaubey says.

There is also the fact of endogamy in the Himalayan populations, given that the mountain range forms a great physical barrier against migration and plays a vital role in shaping population dynamics. While long-term isolation, endogamy and environmental adaptations have been studied for mainland populations, such research for Himalayans is scanty and so the latest study is a step towards more fully understanding their evolutionary biology.

As part of the study, the team measured 10 parameters – body weight, height, BMI, blood pressure, pulse rate, SpO2, hemoglobin, hematocrit, and blood glucose levels.

On average, Sherpas and Tibetans had a mean hemoglobin content of slightly over 12g/dl (14.9g/dl is the control value), while their mean blood pressure was 142/94 (120/80 is the control value). The Bhutias had the highest hemoglobin level (14.23), followed by the Lepcha (13.6).

“Comparatively low hemoglobin in blood facilitates efficient blood circulation in the high altitude populations, enabling them to utilize less oxygen more efficiently,” explains Dr. Rakesh Tamang, the lead author of the study.

Mountaineers speak

Describing these high-altitude people as superheroes, mountaineer Jaahnvi Sriperanbuduru, who holds the record of scaling the highest peaks on four continents by the age of 16, says she has personally seen men, women, children and even aged people living in extreme conditions. “As for Sherpas, their body is built more differently than anyone in the world. Their pulse can drop to the lowest, but it’s just how their body is built and is absolutely normal.”

She and her father, a doctor, have been to mountaineering expeditions together. They often discuss the body structure of those living in the Himalayas. “Unlike Sherpas, we need to acclimatize our body each time we head to a high-altitude environment as we normally live with 100% oxygen,” says Jaahnvi.

Mountaineering coach and National Adventure award-winner Shekar Babu Bachinepally says he always believed that the Himalayan people had it in their DNA to survive in extreme climatic conditions and high altitudes.

“For mountaineers like me, we have to climb high altitudes gradually, allowing the body time to adjust to the decrease in oxygen. The time and the capacity of acclimatization may differ from individual to individual, but giving sufficient time for acclimatization to the lower oxygen levels is the biggest survival technique for mountaineers,” he says, drawing a comparison between mountaineers and Sherpas.

Along with acclimatization, says Shekar, mountaineers need to drink plenty of water to prevent dehydration and altitude sickness, but Himalayan people can do without. “Moreover, we also use a combination of specialized equipment, techniques, and physical and mental preparation to survive in extreme conditions found in the mountains whereas [Sherpas] don’t,” he adds.

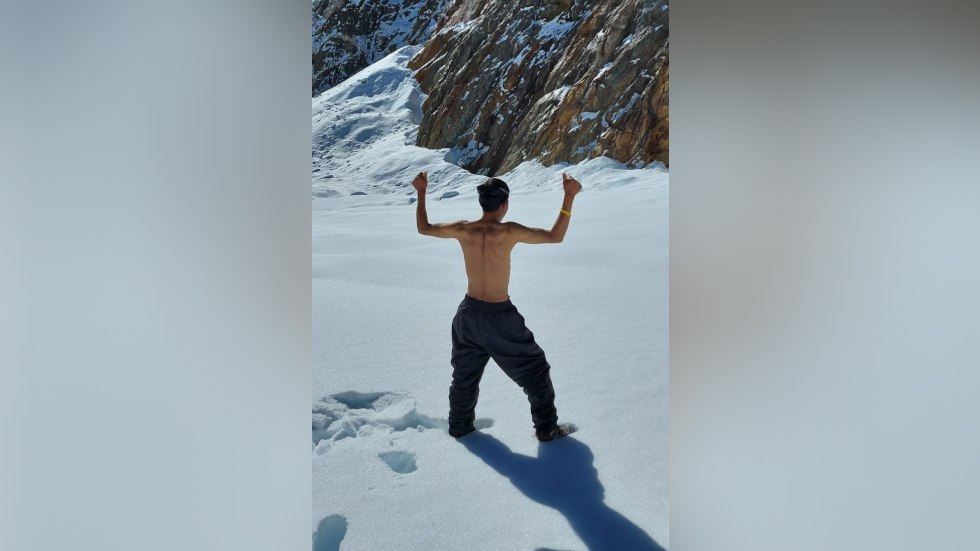

Sameer Nicholas, whose company Adventure Pulse specializes in exotic mountain destinations across the globe, including the Everest Base Camp in Nepal, Elbrus in Russia, and Mount Kilimanjaro in Africa, says one comes across many people living in high altitudes without any issues when traveling through Ladakh.

“Venturing into the remote regions of Ladakh, especially the Zanskar district, I can’t help observe the ruby red sunburnt cheeks of the toddlers, as they play in their mother’s lap, or the young children running through the village paths, where one struggles to walk,” he says, adding that the harsh environment has tempered these indigenous populations to not only survive but thrive over generations.

On the other hand, tourists who fly into the city of Leh immediately experience the effects of high altitude.

Veteran mountaineer Raman Chander Sood, who has closely interacted with Sherpas, Bhutias and other Himalayan people during his mountaineering missions, feels that their capacity to climb the mountains while carrying heavy loads without effort is well-proven.

“I always believed that this happens because they have been born and bred in those conditions, though I knew nothing about the technical side of their blood and [blood pressure] parameters until the latest discovery,” says the 70-year-old, who has been trekking since childhood and climbed peaks across the world.