Who is Narendra Modi, the Indian strongman seeking a third term in the 2024 polls?

If on June 4 the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) wins enough seats in India’s 18th parliamentary election to form the next government, as is expected, and incumbent leader Narendra Damodardas Modi becomes prime minister for the third time, future historians of India may see the era from 1947 to 2014 – from independence from the British colonial raj to when Modi first took office – as a consolidation period for nation-building and a transition period for identity-building.

More than Modi’s personal quest to equal the number of elections won by India’s first PM, Jawaharlal Nehru, the upcoming election is the story of the transformation of India that supporters and detractors alike believe will be irreversible.

Most transformationally, Modi speaks of making India a $5 trillion economy by 2027, from the current $3.5 trillion, and a $35 billion economy by 2047 – the nation’s 100th year of independence. This would mean a mammoth leap in per capita income from $2,612 (nominal, estimated for 2023) to $18,000.

Chaiwala from Gujarat

Modi’s personal narrative plays a large part in his popularity among voters, particularly in northern India, where the majority of the population lives. He was born in a village in northeastern Gujarat, a state that prides itself on its mercantile tradition, into a family that was not in the top tiers of the caste pyramid – India’s stiflingly rigid social structure with strict rules for social interaction and endogamy.

His father, Damodardas Mulchand Modi, owned a tea shop, and the PM early in his electoral career used to claim that he worked selling tea at the Vadnagar railway station. This is an uncorroborated claim that Modi subsequently dropped. There is also a legend that he wrestled a baby crocodile, as told in a biographical comic, Bal Narendra.

In school, Modi was an indifferent student, shining only in school plays and religious pageants like the Ram lila, which are an annual part of small-town life. When he was an early tween, he came across the local branch of the right-wing paramilitary organization, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), and was impressed with its regimen, its morning marches and parades, its daily oaths to Mother India, and its starched khaki shorts. He joined.

Another significant event of his teens was his marriage to Jashodaben, whom he left after three weeks, never to return. Jashodaben became a teacher, and for a long time no one knew that Modi was technically a married man – no divorce was ever sought – until muckrakers dug up this fact after he became the BJP’s candidate for PM (helped, no doubt, by other PM hopefuls in the party). The narrative, set out by biographers, is that Modi wandered the Himalayas in introspection.

These elements are key to Modi’s biographical narrative – his courage, his lifelong loyalty to his organization, his forsaking domesticity for higher things – much in the same way that another Gujarati, known as ‘Father of the Nation’, M.K. “Mahatma” Gandhi, set out his life story: in the four traditional stages of life in the Hindu worldview, Gandhi sought to show that he had reached the final stage of asceticism (and he dressed that way as well).

Rise to PM

Returning to the mundane world, Modi wandered over to the RSS and worked his way up the organization. He went back to school and obtained a bachelor’s degree in “entire Political Science” (his own words, in 2016) from Delhi University in 1978 – his three-year degree course overlapping with former PM Indira Gandhi’s infamous “Emergency” rule, from 1975 to 77, during which civil liberties were suspended and opposition leaders were thrown in jail. Modi spent this period on the run.

In the 1980s, he was seconded to the RSS’s political arm, the BJP, and reached the party’s headquarters in New Delhi. He was deputed for organizational work in the small north Indian states of Himachal Pradesh and Haryana – he was good friends with fellow RSS Manohar Lal Khattar, sitting on the back of Khattar’s scooter; Khattar was selected to be Haryana chief minister in 2014, after Modi became PM, and served for almost a decade.

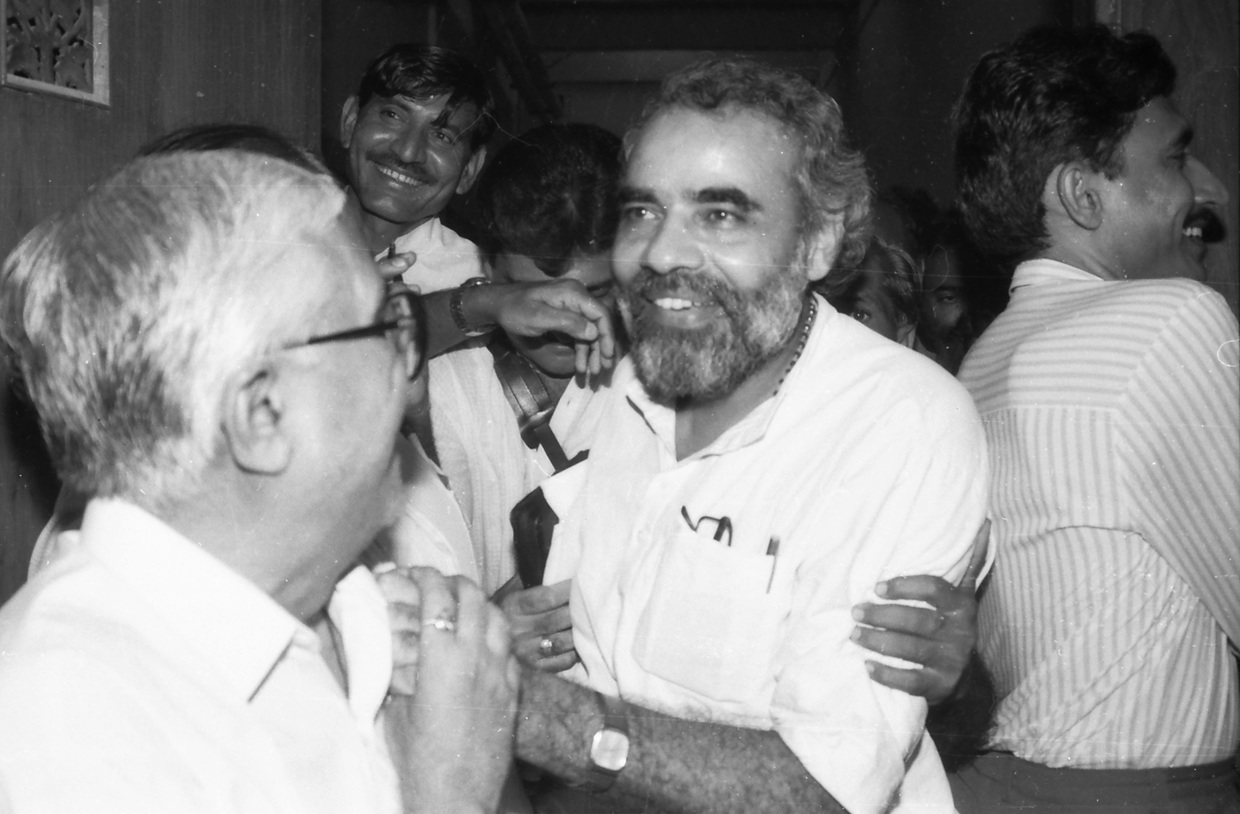

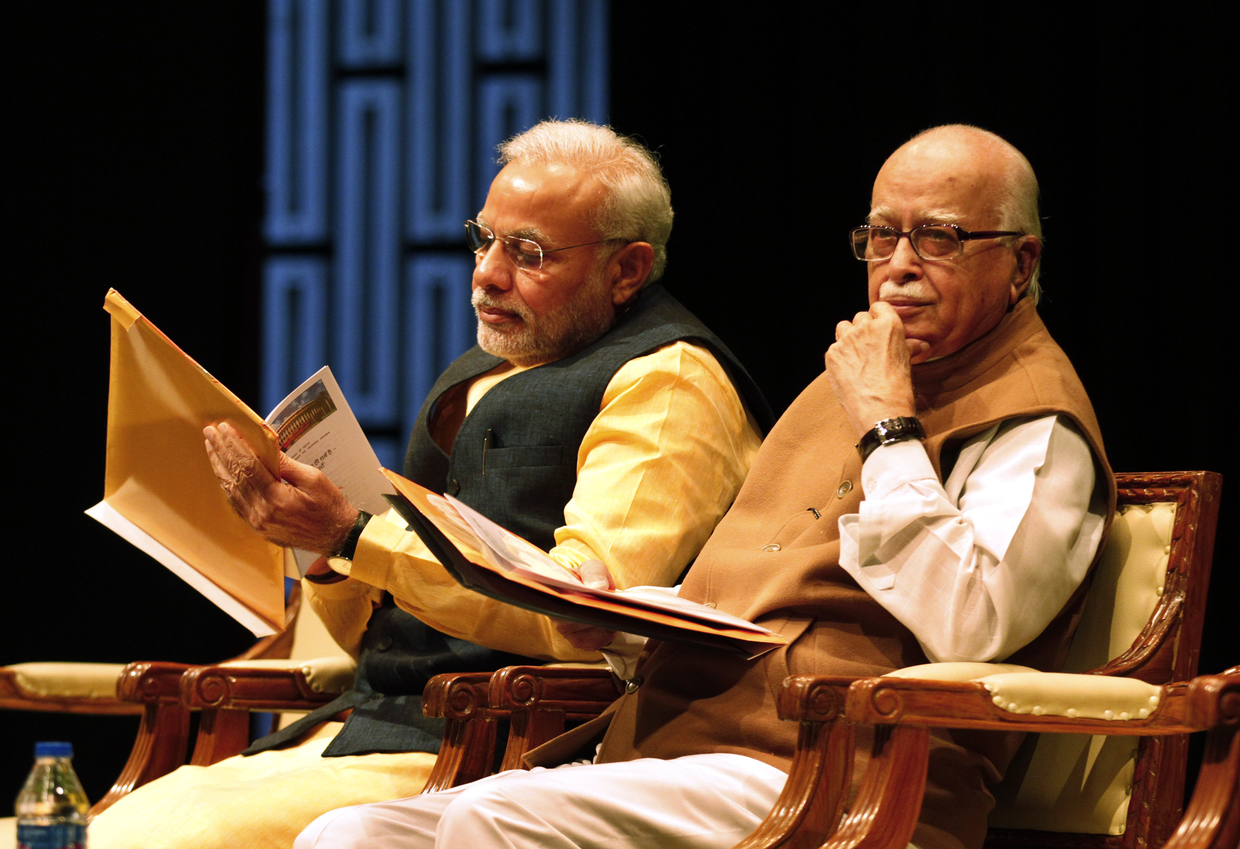

Most importantly, however, is that Modi caught the eye of the BJP president tightly running the party machinery, Lal Krishna Advani, who would be instrumental in Modi’s climb to political power.

This came in 2001, after a major earthquake in Bhuj, Gujarat, in which the incumbent CM, Keshubhai Patel of the BJP, had to step down. Advani sent Modi in his place, despite Modi having no prior administrative experience. Modi made it clear he would not play second fiddle to Keshubhai, and that he would either take complete control or none at all.

Four months later, in February 2002, came an event that defined Modi when rioting broke out all over Gujarat following the burning of a train near the Godhra railway station. The compartment was carrying volunteers involved in the agitation for a Ram Temple in Ayodhya, which had picked up pace since the demolition of the Babri Masjid (standing at the claimed birthplace of mythological Lord Ram) in December 1992. It was passing through a Muslim slum of Godhra when the arson took place, killing 59 passengers.

In retaliation, riots broke out over the next three days all over Gujarat. The official death toll from the violence was 1,053; unofficially, the estimate was about 2,500. The perception was that Modi had allowed it to happen, including the brutal murder of a former Congress parliamentarian, who allegedly telephoned Modi as a mob was standing outside his house. The Supreme Court later exonerated Modi.

However, Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee was unhappy with Modi’s “handling” of the riots, and wanted him to resign, publicly reminding him of his “raj dharma” (king’s duty). But Advani prevailed upon Vajpayee to let Modi remain, and in the next state legislative election – the first led by Modi – returned him to power overwhelmingly.

Modi has never regretted the riots or his role – it was now his “brand,” and drew a significant number of Hindus to support him. Despite being CM, he had to suffer the indignity of being denied a visa to the US and of being overlooked at meetings by national industry bodies, but one modest Gujarati businessman came to his rescue. Gautam Adani organized several Vibrant Gujarat business summits, showcasing Modi as a development genius.

When the party was looking towards the 2014 parliamentary election, there was no mood for the old warhorse Advani, who had lost the 2009 election. Instead, BJP leaders found that all over the country, people spoke of Modi leading the party. His “brand” found more appeal in an increasingly polarized geopolitical environment. And after fatigue with the Manmohan Singh government that had been in power for a decade, the BJP, led by Modi, won a majority of parliamentary seats – the first time any party had done so since 1984 (when the late Rajiv Gandhi swept the polls after his mother Indira’s assassination).

Decade of reforms

With this mandate, Modi began implementing the very things that the RSS had been saying was on its agenda since independence. The first was a fiscal conservative approach, in which the government’s priority was to enable private industry to lead the economy. Its two favored industry strongmen were Gujarat’s biggest industrialists – Adani and Reliance Industries head Mukesh Ambani.

In November 2016, Modi suddenly demonetized high-value currency. His government gave a variety of reasons – to fight black money, to fight counterfeiting, to bring down currency in circulation, to fight terrorism, to facilitate the shift to a digital payment system – but in hindsight, none of these were achieved. Instead, four months later, the campaign began for Uttar Pradesh (UP), India’s largest state. The BJP opponents, who were believed to have had significant cash on hand for on-the-ground spending, were left with useless paper, and the BJP won resoundingly. In Indian politics, the way to Delhi is said to be through UP.

That terrorism did not end was evidenced by the February 2019 attack in Pulwama in the border state of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K), where 40 paramilitary personnel were killed. Modi retaliated by sending fighter jets across the border, showing that his government was not shy to fight back. It helped him win the parliamentary election two months later, with an even bigger majority, and a momentous second term.

On August 5, 2019, he fulfilled a long-standing right-wing demand to end the special Constitutional status of J&K, dividing it into two Delhi-controlled union territories. Shortly thereafter, the Supreme Court of India allowed the building of the Ram Temple in Ayodhya, which was inaugurated by Modi in January 2024 and widely celebrated across the country.

Along the way, Modi has taken several measures to centralize power. He is in a tug-of-war with the Supreme Court over legislation to let the government have a decisive say in the appointment of judges (it is currently done by a consortium of judges). He has changed the rules of appointments to the Election Commission, removing the Chief Justice of India from the three-member appointments panel and replacing him with a government minister.

He has done away with the Planning Commission, set up by India’s first PM, and replaced it with a Niti Aayog; the Commission was a legacy of PM Nehru to formulate five-year plans, as was done in several centrally-planned economies globally, for long-term economic planning and development. He has weakened the states by eating away at their share of revenue, collected through the Goods and Services Tax (GST). He has built a new parliament, even though opposition parties claim they were not consulted.

Central agencies have gone after the government’s political opponents in the states.Under India’s constitution, policing is a state subject, and earlier, the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) could only operate in a state if the local government invited it. Now, the National Investigation Agency (NIA) and the Enforcement Directorate (ED) act unimpeded by the state governments.

In the current campaign, Modi has said this is because of his drive against corruption, but the Supreme Court this year allowed the public to see the details of the Electoral Bond scheme, something hatched by Modi’s first government. Out of $1.9 billion collected, 47% went to the BJP – from companies which had just been raided by the ED, or were threatened with legal action, or which within days were awarded lucrative contracts and tenders.

Even within his own party Modi remains first among equals. Government decisions are said to originate from the Prime Minister’s Office, as opposed to individual relevant ministries. The recent distribution of party nominations to contest the upcoming parliamentary election sent a message: all are dispensable.

Work in progress

It has not all been smooth sailing for the government. A Citizenship Amendment law – ostensibly to allow Hindu refugees to settle in India – was passed but is yet to be implemented due to protests around the country. Unemployment remains a persistent problem, particularly among the youth. The economy has recovered since the Covid-19 pandemic, better than many countries in the world, but not enough to catapult India into the league of China – the middle-class Indian fantasy.

China is India’s biggest foreign policy problem. In June 2020, Indian and Chinese troops clashed in the Galwan Valley of the high-altitude mountainous Ladakh region. Twenty Indians and four Chinese soldiers died. Modi has been unwilling to admit what satellite maps show – that land that earlier lay in the no-man’s area on the Line of Actual Control (LAC) has now been usurped by China.

It has also meant that Pakistan is no longer India’s top geopolitical problem, reflecting the private view in right-wing circle that Pakistan is best kept in deep freeze for an extended period.

The big domestic headache of recent times was the Manipur violence that began in March 2023 and has cast a shadow over the election in the northeastern hill state. Modi has not visited the state once since the violence erupted – over constitutional rights for different groups in the state – but he recently asserted to a local newspaper that his government intervened in a timely manner to save the situation. Indeed, the major victims of the violence – the Christian hill tribes known as the Kuki-Zo – have announced they will boycott the election.

The thing that matters most – as shown by a recent survey by the Centre for Study of Developing Societies (CSDS) – is that India’s identity as a Hindu country has been consolidated. People may not plan to visit the Ram Temple, but they express happiness it was built.

If reelected, Modi knows what is expected of him: a transformational phase in Indian history. India already has nuclear power, a space program, heavy industry, world class universities, big infrastructure like dams and bridges – all of these were part of the nation-building that took place in 1947-2014.

What India, and therefore Modi, now aspires to do is to forge a sharp Hindu identity whose presence is noticed in the world – be it cultural, linguistic, economic or political.